The treatment of people based on the color of their skin is front and center in American life right now. From law enforcement, to pay equity, to hiring practices these differences can be seen plain as day across most areas of life. While college basketball is certainly more diverse than many areas of American life, there are still differences in dynamics of how Minority and White coaches are hired, and how they move around within the coaching ranks.

This topic has been addressed in a number of ways over the past few years. However, while similar in topic, the scope of this piece is a bit different: how career progression differs between Minority (ie non-White) and White coaches. Specifically, do Minority and White coaches enter the D1 coaching ranks at an equitable level? Is the pathway to becoming a head coach harder for Minorities than it is for White coaches? Once an individual becomes a head coach, is it harder to get a second head-coaching job for Minorities vs. White coaches? Do Minority coaches tend to get their first head-coaching gig at conference lower levels than their White counterparts do?

For the purposes of this article, White coaches are defined as Caucasian, non-Hispanic or Latino individuals. Minority coaches consist of the remainder of coaches not included in the definition of White coaches. In this dataset, that includes Black, Latino, Asian, Native American, Middle Eastern, and Indian coaches.

According to 2019 US census estimates, roughly 40% of the US population is Minority, and 60% of the US population is White. Data available on the NCAA website shows that during the 2018-2019 men’s basketball season approximately 77% of men’s basketball athletes were Minorities, and 23 % of men’s basketball athletes were White.

While the player population is overwhelmingly comprised of Minorities, those percentages do not carry over to the coaching ranks. Looking at all NCAA D1 head coaches from the 2007/2008 through 2019/2020 seasons, 34% of head coaches were Minorities, while 66% of head coaches were White. Those percentages, however, are crude in that they do not account for coaches who have longer careers. For example, Leonard Hamilton’s 18+ season’s at Florida State weigh the same as Travis Steele’s 2+ seasons at Xavier.

One way to account for that would be to look at total seasons coached by Minority and White coaches, and divide by the total number of seasons coached overall in the entire data set. This more granular look paints a much starker picture. Since the 2007/2008 season, 22% D1 men’s basketball seasons were coached by Minority head coaches, while 78% of seasons were coached by a White head coaches. Perhaps ironically, the season-adjusted percentages for coaches (22% Minority vs. 78% White) are almost the mirror opposite of the player population (77% Minority vs. 23% White).

Moving down the bench, the racial discrepancies become less severe. Minority coaches over the same time period account for 46% of assistant coaches compared to 54% for Whites. Adjusting for total seasons coached, the balance tilts a bit towards White coaches (44% Minority, 56% White), but not nearly as much as seen with head coaches. Table 1, below, summarizes these percentages.

Why is this? Why are there so few Minority head coaches compared to players and assistant coaches? The discrepancy is particularly noticeable when you consider that the pipeline to a head coaching position (assistant coaches), is more equitably split between Minorities and Whites. That discrepancy alone implies that the pathway to a head coaching position is truly more difficult for Minority coaches than it is for their White peers.

The Carousel Analytics database includes the entire career history of every head and assistant basketball coach at the D1 level since the 2007-2008 season. In order to look at these questions in depth, race was added as a variable in the Carousel Analytics database. To ensure comparisons were apples-to-apples when answering the questions listed above, only coaches who ultimately became D1 men’s basketball head coaches at any point in their career were included in the analysis dataset.

The resulting dataset included 825 unique coaches (35% Minority, 65% White), encompassing 1358 head coaching jobs and 8379 seasons coached. Quick note, the Carousel Analytics database does include women who were men’s D1 basketball coaches. However, there have been no female D1 men’s basketball coaches who became head coaches, therefore no women are included in this work.

First we will look at whether there is a difference between Minority and White coaches in terms of their first job on a D1 coaching staff. This includes any job as a member of a basketball staff after graduation. For example, student athletes and student managers are not included. However, graduate assistants and other support staff roles are included. Titles such as Director of Player Development, Director of Recruitment, Special Assistant to the Head Coach, Video Coordinator, etc… were lumped into the Support Staff (SS) category. Lastly, this does not include first jobs that were outside of the D1 level (D2, D3, Pro, etc…). If a coach was a D3 assistant for 5 years before becoming a Graduate Assistant at the D1 level, their first job would be considered a Graduate Assistant.

Figure 1 shows the percent breakdown, by race, of where coaches landed their first job at the D1 level. The big takeaway from Figure 1 is that when it comes to first jobs at the D1 level, a similar percentage of Minority coaches jump straight into a Head Coach job as their White counterparts (8.4% vs. 8.3%). For individuals whose first D1 job was as an Assistant Coach, Minority coaches appear to start at the assistant coach level more frequently than White coaches (73.8% vs. 67.9%). Looking at jobs that are lower down the coaching ranks, White coaches tend to start their careers as a DOBO, GA, or SS member frequently than their Minority counterparts.

Figure 2, below, takes the same data as above and breaks down whether those first jobs are being taken at low, mid, or high major schools. The left panel shows data for Minority coaches, and the right panel shows data for White coaches. Beginning with the head coach position, it is noticeable how similar the percentages are between Minority and White coaches. Both groups enter the D1 world as a head coach at the low major level around 4% of the time. There is a slight difference at the mid and high major levels, where Minority coaches enter at those levels 2.4% and 1.7% of the time compared to 3.5% and 0.7% for their White peers.

Moving down the bench to those who entered the D1 coaching world as an assistant coach, we start to see some more noticeable differences. A much higher percentage of Minorities start as a Low Major Assistant Coach (28.3% vs. 18.4%). That gap narrows at the mid major level (35% vs. 32.3%), and is flipped in favor of White coaches at the High Major level (10.5% vs. 17.3%). Again, White coaches tend to enter the coaching ranks at the DOBO/GA/SS level more frequently and at a higher conference level than their Minority counterparts. The key takeaway here is that other than first jobs as a head coach, Minority coaches usually enter the D1 coaching world at a lower conference level than White coaches.

Shifting the focus away from first jobs and towards entire careers, Figure 3 shows the percentage of low, mid, and high major head coaching jobs taken throughout a coach’s career.

Minority coaches tend to get their first head coaching job at the low major level more often than White coaches (51% vs. 45%), while White coaches tend to enter at the mid major level more often (48% vs. 40%). White and Minority coaches who get their first head coaching job at the high major level tend to do so at the same rate.

A higher percentage of Minority coaches stay at the low major level for their second head coaching job compared to White coaches (32% vs. 17%), while a smaller percent of Minority coaches reach the mid major level (32% vs. 46%). Meanwhile, the percentage of Minority and White coaches who have their second head coaching job at the high major level is roughly the same (36% vs. 37%).

After their first head coaching job, the percentage of Minority coaches who stay at the low major level slowly decreases, though it is consistently higher than White coaches. That is, until the fourth head coaching job when the number of observations starts to decrease significantly. At the mid major level, there is consistently a higher percentage of White coaches until the fourth head coaching job. There is a similar trend for high major jobs, where the percentage of White coaches who move up to the high major level is typically higher, and increases at a faster rate, than it does for Minority coaches.

In terms of how much experience a coach needs to get their first head coaching job, there is evidence of a slight difference between Minority and White coaches. Figure 4 shows how many years of “core” staff experience a coach typically has before earning their first, second, third, and fourth head coaching job. “Core” staff experience is defined as experience as a D1 Head or Assistant coach. Each segment connecting a green and orange dot represents a single coach. No data is shown for fifth, sixth, or seventh jobs due to low numbers within each subgroup.

On average, Minority coaches needed 8.87 years of core staff experience prior to getting their first D1 head coaching job. Meanwhile, White coaches needed less core staff experience (8.1 years) prior to getting their first D1 head coaching job. While that may not seem like a big difference, ¾ of a year of experience means White coaches need roughly 8% less experience than Minority coaches prior to getting their first head coaching job.

As you would expect, there is a knock-on effect due to Minority coaches starting their head coaching careers later than White coaches. Minority coaches tend to need more experience prior to starting their second head coaching job than their White counterparts (14.86 vs. 13.53 years). We start to see a narrowing of this gap around the time of the third head coaching job. Minority coaches need 20.41 years of core staff experience compared to 19.41 years of core staff experience for White coaches. However, the gap grows again for the 4th head coaching job where Minority coaches on average have 25.07 years of core staff experience prior to getting their 4th job, while White coaches average 21.31 years of experience.

The natural follow-up question to this is to ask whether Minority and White coaches stay in their head coaching jobs for the same amount of time. Looking at only head coaching jobs, Figure 5 shows that across an entire career Minority coaches on average stay at their job for 5.26 years. Meanwhile, White coaches stay at their job for 6.32 years on average.

Looking more closely, it is clear that Minority coaches have shorter tenures at each head coaching job throughout their career. The only exception is during the third head coaching job. On average, Minority coaches in their third head coaching job have a longer tenure than White coaches (5.69 vs. 5.16 years). The longer tenure for Minority coaches during their third head coaching job is driven by a few coaches with unusually long tenures during their third job: Leonard Hamilton (18 Years and counting at Florida State), Lorenzo Romar (15 years at Washington), and Tommy Amaker (13 years and counting at Harvard).

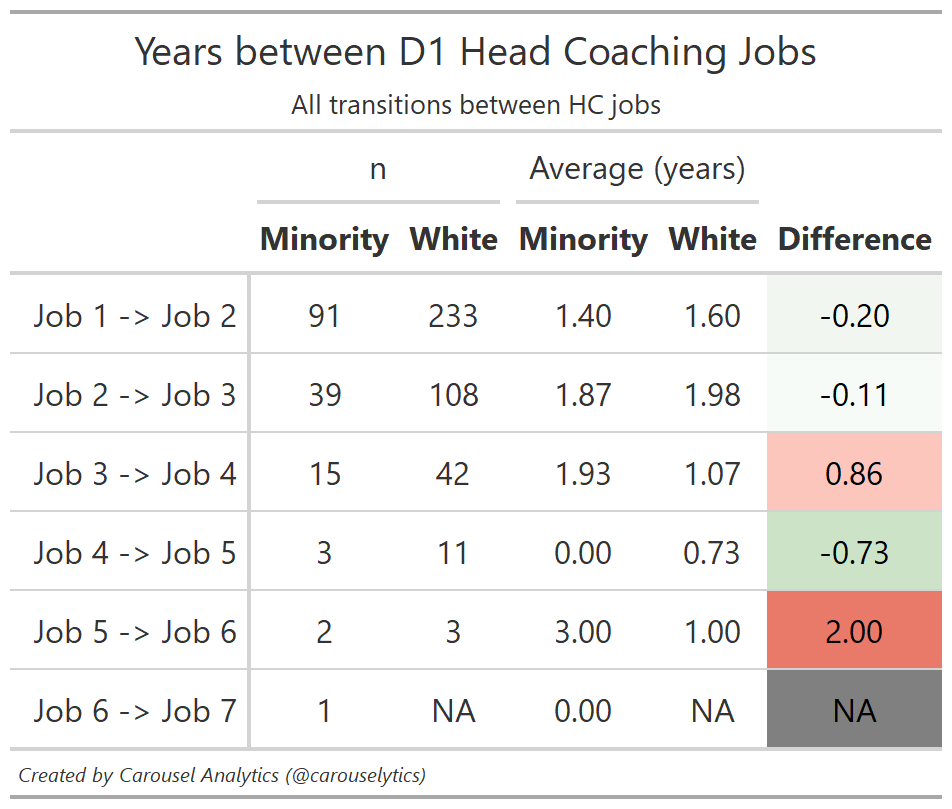

Finally, we can look at whether there is a difference between Minority and White coaches in terms of how many years they have to wait between head coaching jobs. Table 2, below, shows the average number of years between head coaching jobs for Minority and White coaches. There is no consistent evidence of a difference here between Minority and White coaches. The transition between jobs 1 and 2, and between jobs 2 and 3, were very similar between Minority and White coaches. Minority coaches did have longer gaps between jobs 3 and 4 compared to White coaches, but that difference flipped back at the next job interval.

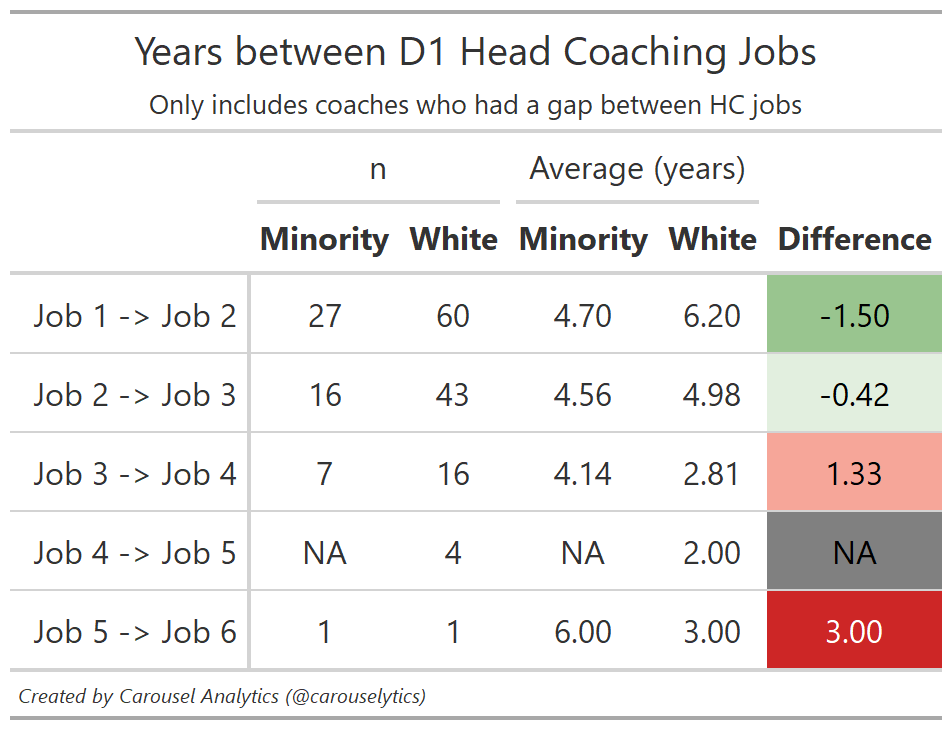

The previous table included all coaches in the dataset who had more than one head coaching job, regardless of whether there was a gap between head coaching jobs. While many coaches move between head coaching jobs without time off between jobs, in reality some coaches do not move directly from one head coach job to another. Instead, they spend some time as an assistant coach, or on TV, or just away from the game for a bit.

Table 3 shows the average number of years between head coaching jobs, this time including only coaches who had time off between head coaching jobs. The idea behind this table is to see if Minority and White coaches who do not transition directly to another head coaching job have a harder time getting back to the head coaching ranks. Again, there is no discernable pattern. Instead, it could be argued that Minority coaches have an easier time jumping back into head coaching jobs after some time away from head coaching than White coaches.

All of this can be put together to paint a clear picture of how career progression is different for Minority and White coaches. There are many more Minority players than White players, there are similar numbers of Minority and White assistant coaches, but there are many more White head coaches than Minority head coaches. Despite having similar first jobs at the D1 level, Minority coaches tend to start at the low major level more often, and White head coaches are able to move up to higher conference levels more easily than their Minority peers.

Minority coaches need more core staff experience prior to getting their first head coaching job, as compared to their White counterparts. That discrepancy maintains itself and gets more pronounced throughout a coach’s career. In addition, Minority coaches have shorter head coaching tenures throughout their career than White coaches. However, there is no difference between Minority and White coaches when it comes to how long they have to wait between head coaching jobs. If anything, Minority coaches are able to jump back in to head coaching jobs more quickly than White coaches do.

These data do not exist in a vacuum. There is a compounding effect between the increased amount of experience that a Minority coach needs prior to each head coaching job, and the decreased tenure that Minority coaches have at most head coaching jobs in their career. If Minority coaches need more experience prior to each head coaching job, but they also have shorter tenures once they do get head coaching jobs, that means they have to spend increasingly more time as an assistant coach prior to getting their next bite at a head coaching job. Across an entire career these factors add up to create more resistance to upward mobility for Minority coaches.

In spite of a huge population of Minority basketball players at the D1 level, and an equitable number of Minority vs. White assistant coaches, there is a clear discrepancy in how Minority coaches are able to climb up to head coaching positions. For whatever reason, White coaches are able to move upwards more easily, and stay there longer. In order to address these issues, it is necessary to develop regulation and/or programs to ensure that Minority coaches are given equal opportunity to advance their careers. The status quo is simply not enough.