Staff turnover at the NCAA men’s basketball division 1 level is par for the course. If you add up all of the head and assistant coach seasons from 2007-2019 there were 16,686 seasons coached. In those 16,686 seasons, 4124 ended with a job change either by promotion, demotion, or moving to a new school. In other words, roughly 1 in 4 coach-seasons ends with a coach changing jobs. Put another way, on a staff of four, odds are one coach will leave every season.

Job turnover in D1 NCAA basketball coaching ranks is pervasive, and something that should be expected and planned for. It is also something that happens regardless of team success. If a team has a terrible season then there is a decent chance that the head coach will be fired and the entire staff will be replaced. If the head coach is not fired, then the assistant coaches may be on the lookout for jobs elsewhere to avoid being associated with a bad program. On the other end of the spectrum, head and assistant coaches for successful teams have options to move up and/or earn more money at schools willing to pay a premium for their services. Both Athletic Directors and Head Coaches need to be prepared for staff turnover and have an idea of what they are willing to do to keep their staff intact. But how much emphasis should leaders place on keeping their staff intact for multiple years? In this article, I aim to explore the impact any loss in staff continuity on team success, in this case using efficiency margin as a measure of success.

(If you have not already done so, now would be a good time to take a look at my previous post here.)

To look at this, I am defining staff continuity as the number of years that a Head Coach (HC) and his/her Assistant Coaches (AC) have stayed together without any turnover. I set a few parameters to ensure the comparison is apples to apples, specifically:

- Only the 2007-2008 through 2018-2019 seasons are included.

- Only core staff (HC and AC) are included in the continuity calculation (No DOBO, DOPD, etc…).

- Only staffs with three or more “core staff” members (HC and AC) are included.

- Associate Head Coaches are combined with the AC group.

Two quick notes: 1) Internal promotions, for example if a DOBO is promoted to replace a departing AC, do not extend staff continuity. 2) For staffs with multiple years of continuity, each season is treated as unrelated to other season and each season is included in the data. For example, a staff with five years of continuity is included five times.

Once all the parameters are applied there are 4167 team-seasons included in the dataset. The vast majority of these coaching staffs have four core members (n=4008). There are a few schools that have more than four staff members due to turnover within a season, where a coach leaves and is replaced by a support staff member for the remainder of the season. While this increases the amount of staff, continuity is reduced to 1 in those instances. Service academies (Army, Navy, Air Force) frequently have more than four core staff members.

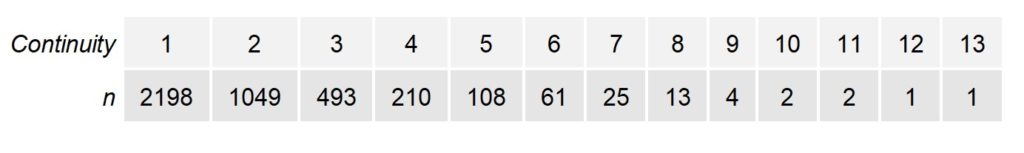

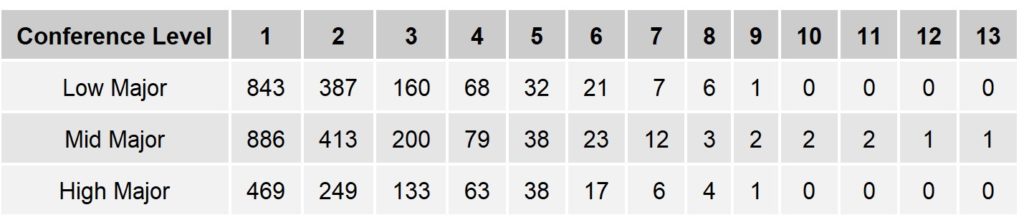

Looking at staff continuity, the data skews sharply towards one year of staff continuity. In the past 12 seasons of men’s D1 basketball, 2198 out of 4167 teams had their staff together for only one season. In the same time-span, only 108 teams held their staff together for 5 years. Two teams kept their staff together for 10 years. One school had their core coaching staff together for 13 years in a row (St. Joseph’s, whose streak ended with the firing of Phil Martelli following the 2018-2019 season). You can see how difficult it is to keep a staff in place for more than one year, let alone five years, ten years, or more.

To look at the impact of staff continuity on team success I am again using efficiency margin, defined as points scored per 100 possessions minus points allowed per 100 possessions across an entire season. I am using efficiency margin instead of wins due to the fact that not all schools play the same number of games, and a late season run (or collapse) might mask the achievements of an otherwise good/bad team.

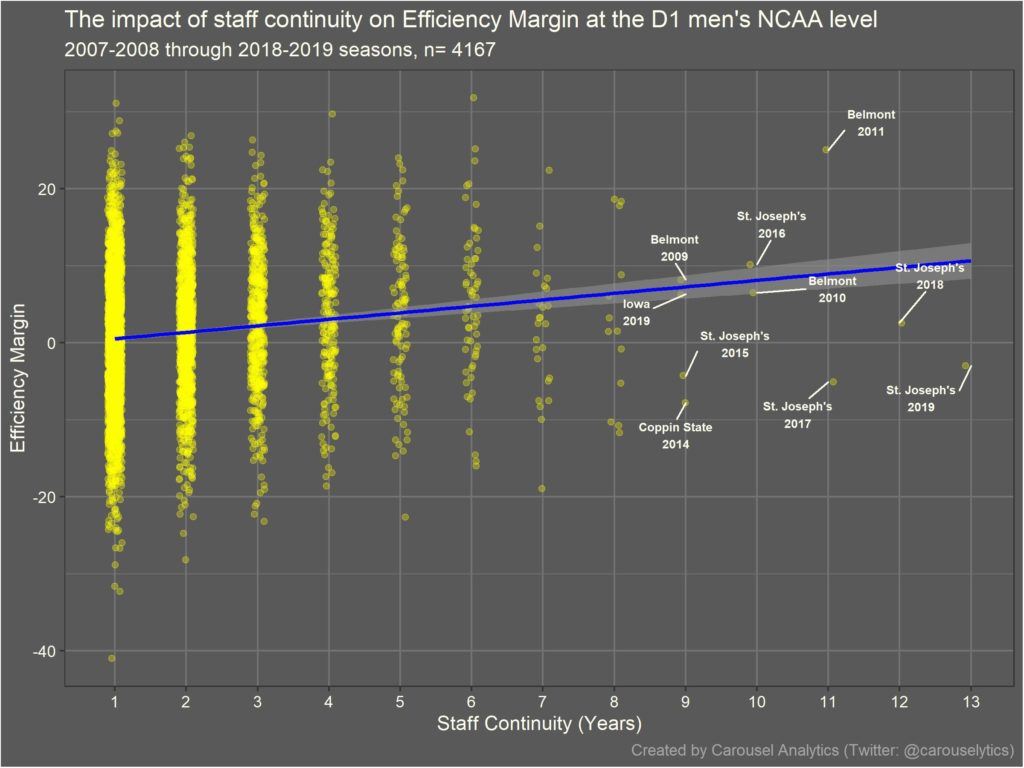

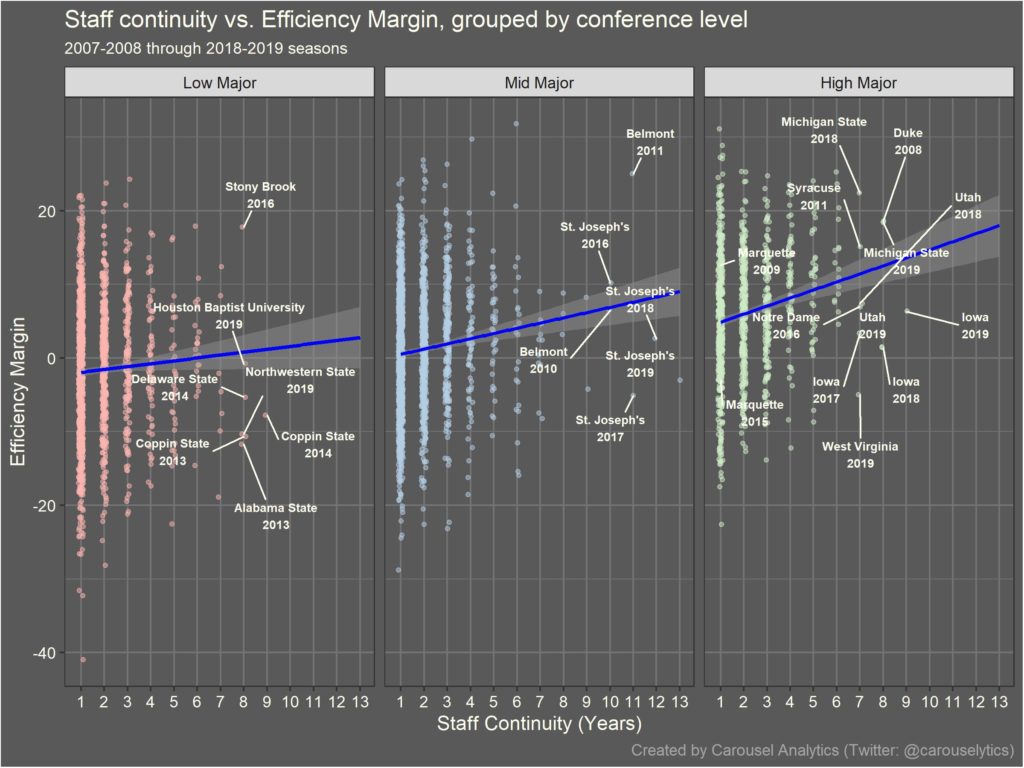

Plotting staff continuity against efficiency margin shows that there is a relationship between the two (see Figure 1, below). To the naked eye, staffs that stick together for a long time have a slightly higher efficiency margin than staffs that have been together for fewer years. A quick linear regression model, represented by the blue line, confirms that staff continuity does have a significant relationship with efficiency margin (p<0.05). In more practical terms, every year of staff continuity added results in an increase in efficiency margin of roughly +.85 over the course of a season.

Glancing at the schools with 9 or more years of continuity, most of them are low or mid-major schools with Iowa being the only high major program to have a staff with at least 9 years of continuity. Iowa had turnover at end of 18/19 season, but Michigan State and West Virginia will have 9 and 8 years of staff continuity at the conclusion of the 19/20 season, respectively. While conference level is somewhat subjective, using conference level as a grouping category is a useful way to compare schools that are similar in terms of resources.

Breaking down the data even further to see how this relationship plays out in low, mid, and high major conferences provides more context to the relationship between staff continuity and efficiency margin. The table below shows the same information as the staff continuity table above, except it controls for conference level. The same trends are present as before, mainly that it is very difficult for schools to keep their staff intact from season to season.

Looking at the data by conference level shows some interesting results, shown in Figure 2 below. The relationship between staff continuity and efficiency margin is maintained across all conference levels. There is a significant increase in efficiency margin with increased staff continuity for low major (p=0.02), mid-major (p<0.01), and high major (p<0.01) conferences. Of note, the impact of staff continuity is stronger as conference level improves. Not controlling for any other variables, a one unit increase in staff continuity leads an average increase in efficiency margin of +0.40, +0.71, and +1.1 at the low, mid, and high major conference levels, respectively. Extending that a bit, if a staff stays together for 5 years, they have on average an efficiency margin increase of roughly +2, +3.5, and +5.5 for low, mid, and high major programs, respectively.

What does this all mean? First off, staff continuity is an important factor to consider when deciding how to change or improve a team’s staff each year. Change for change’s sake is probably not worth it. Second, staff continuity seems to have a stronger relationship to efficiency margin as conference level gets higher. Coaching talent matriculates upward and stays there. If a coach has the opportunity to move up to a higher conference level where they receive higher pay and have access to better resources, they will probably take that opportunity. However, coaches at low and mid major schools are competing with each other for the opportunity to move up, in addition to competing with high major coaches who change jobs while staying at the high major level. As talent does filter up, the impact of more abundant, high quality coaching becomes more apparent and is amplified by staff continuity leading to increased success. This could also explain the smaller impact of staff continuity on efficiency margin at the low and mid-major levels – the good coaches are the ones that readily move up, leaving a lower quality of coaching at lower conference levels. No offense intended to coaches in low and mid-major conferences.

Of course, many factors influence team success and they are not all being taken in to account at the moment. Staff continuity does not exist in a vacuum, and many things influence whether a team is good or not. Specifically, a similar player-centric roster quality and roster continuity measure would have a strong relationship to team performance. There is a lot of variability in the efficiency margin for teams at each level of staff continuity. A portion of the variability at 1 year of staff continuity could be due to staff turnover that results in very little or very much roster turnover. If we randomly select a school that has had a Head Coaching change in the past 12 years, let’s say Marquette University, we can do a quick case study on how a roster can impact team performance the year following a coaching change. Following the 2007-2008 Buzz Williams replaced Tom Crean as Head Coach, and inherited a team returning four high level and highly experienced players (3 seniors, 1 junior). Coach Williams and his coaching staff were able to find immediate success (+12.6 Efficiency Margin, 25 wins, lost in NCAA Round of 32). On the other end of the spectrum, when Buzz Williams departed for Virginia Tech following the 2013-2014 season he left behind a roster with a few low-impact seniors, and a few decent but not great young players. New Head Coach Steve Wojciechowski’s staff was not able to find immediate success (-3.0 Efficiency Margin, 13 wins, no post-season tournament). Both of these Marquette teams are highlighted in Figure 2.

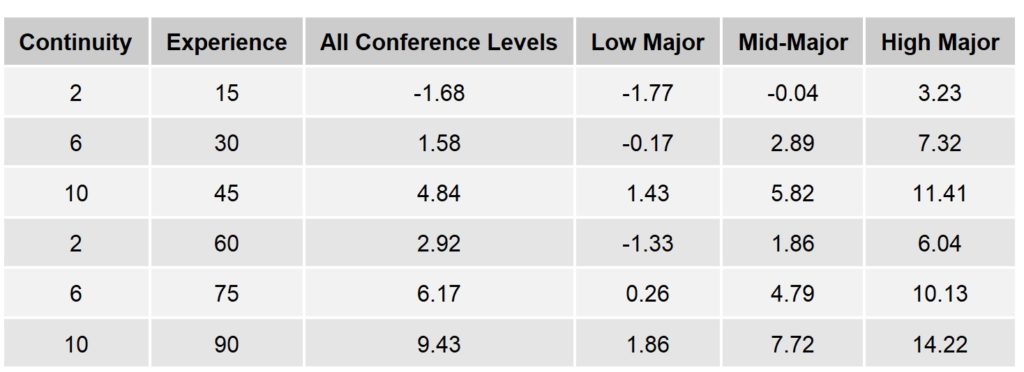

I am not going to dive deeper into other variables that influence team success at this time. That said, I am going to incorporate some of my previous work showing that staff experience is significantly related to team success. Without controlling for conference level, after adding staff continuity and staff D1 men’s core experience to the model both remained significantly related to efficiency margin (p < 0.01). The results vary a bit when controlling for conference level. At the low major conference level neither staff continuity nor staff D1 men’s core experience are related to a change in efficiency margin. For mid-major and high major schools, both staff continuity and staff D1 men’s core experience remained significantly related to an increase in efficiency margin (p < 0.01).

Table 3 shows how an increase in staff continuity and/or staff D1 men’s core experience relate to an increase in efficiency margin at each conference level. This table represents how predicted efficiency margin changes as staff continuity and staff experience are manipulated, across four conference level groups (all levels, low major, mid-major, and high major). Note, staff continuity increases from 2, to 6, to 10 years, then repeats, while staff experience always increases in increments of 15 years. The purpose of that is to show how a higher level of staff experience can help offset the impact of decreased continuity on efficiency margin. For example, a mid-major team with 2 years of staff continuity and 15 years of staff D1 men’s core experience would expect an efficiency margin of +0.17; while a team with the same staff continuity but 60 years of staff D1 men’s core experience would expect an efficiency margin of +6.15.

While it is tempting to use this as a predictive tool, I don’t think that’s the best way to use this information. The variance at each year of continuity, particularly in the low continuity years despite the large sample size, makes it difficult to develop this as a predictive tool at this point. Instead, it is best used as a comparison tool to see how staff continuity and staff experience compare and interact with each other in regards to efficiency margin.

How can this information be used to inform the hiring decisions of Athletic Directors and Head Basketball Coaches? Both staff continuity and staff experience have a significant impact on team performance at the mid and high major levels, but not at the low major level. While both staff continuity and staff core experience are important, either can be emphasized to gain an edge.

For example, a mid or high major Athletic Director or Head Coach deciding how to maintain or build a coaching staff would benefit from spending resources to keep a successful coaching staff together if possible. It is more difficult to keep a quality staff together than it is to find an experienced replacement. If you cannot keep your staff together, or if the cost of keeping your staff together is prohibitive, then you should focus on replacing the departing member(s) of your staff with a lower cost assistant coach with a lot of experience to help offset the loss of continuity. Finding a coach who fits that mold, and has a history of staying at one school for more than a couple years would also benefit long-term team performance. Finally, spending a small amount of capital during each season to develop a list of both head and assistant coaches who fit the experience and cost profile of your program would benefit any Athletic Director or Head Coach. This list would give institutional leaders an idea of who is available or likely to become available, and how difficult and/or costly it would be to find a replacement that would offset the lost staff continuity.

In Part 2 I will explore how different levels of continuity impact team success. So far I have treated all amounts of staff turnover the same – whether the entire staff leaves or only one staff member leaves. Part 2 will also look at the impact of losing one staff member vs. losing two, three, or all four staff members, and will look to see if staff experience or institutional experience can help bridge the gap when staff turnover occurs.

Thanks for reading.

Steve